For someone who famously declared: "History is bunk" his construction of what is formally called The Edison Institute (but better known by its constituent parts of the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village) seems inconsistent but he preferred to see history in the accomplishments of the everyday rather than the works of Great Men. Hence, his declaration on the rationale for the Institute: "I am collecting the history of our people as written into things their hands made and used.... When we are through, we shall have reproduced American life as lived, and that, I think, is the best way of preserving at least a part of our history and tradition..."

The museum, which is referred to as "the Henry Ford," is a 12 acre building modeled on Independence Hall in Philadelphia, and which contains an absolutely eye-popping collection of antique machinery, automobiles, locomotives, steam engines, airplanes, and odd items of popular culture. The exhibition space totals nine acres. It was finished in 1929 but only opened to the public in July 1933 and receives 1.6 million visitors along with Greenfield Village each year. There are separate admission charges for the two attractions and on this day we just did the museum.

We entered the museum at the exhibit devoted to Presidential vehicles, which ran from Theodore Roosevelt's 1902 coach (he did not like cars, apparently) to the 1972 Lincoln Continental limousine used by Ronald Reagan. The most noteworthy of the five vehicles on display is, of course, the 1961 Lincoln Continental in which President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963 in Dallas. This car, which was not armoured, was retained in government service until 1977 but considerably modified with titanium armour and a permanent roof.

|

| 1939 Lincoln Presidential limousine, "the Sunshine Special," used by Franklin D. Roosevelt |

|

| 1950 Lincoln Presidential limousine built for Harry S Truman but more closely identified with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who added the distinctive plastic bubble top |

|

| 1961 Lincoln Continental Presidential limousine, one of the most famous cars in history |

Leaving the Presidential vehicles, we found ourselves in "Heroes of the Sky," perhaps the best assemblage of historically-significant aircraft in the United States after the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum, although admittedly on a smaller scale.

Henry Ford was a pioneer in commercial aviation and his Ford Trimotors, built from 1925 to 1933, was an important step in aviation by offering a reliable, rugged, all-metal aircraft suitable for airline use. By the late 1920s, the Ford company was considered the largest manufacturer of commercial aircraft in the world although in the end Ford made no money with its airplane subsidiary. On display is the "Floyd Bennett," a 1928 Trimotor used by the Byrd Expedition for the first flight over the South Pole on November 28.29, 1929.

|

| Ford Trimotor with contemporary Chrysler Imperial |

In addition to not making money in the airplane business, Henry Ford was apparently distressed by the death of his test pilot and close friend, Harry Brooks, in the crash of the Ford Flivver, in 1928. This airplane was meant to be an everyman's airplane, a flying Model T, and Brooks set several speed records in its weight category. Charles Lindbergh was the only other person to pilot one of the five Flivvers built and he described it as "one of the worst aircraft he ever flew." The Flivver in the museum is the sole surviving original and two replicas have been constructed. Surprisingly, another attempt was made to build a mass-market airplane by Ford but the flying wing design 15P, powered by a Ford V-8, and completed in 1936, never advanced beyond a single unsuccessful prototype.

|

| 1926 Ford Flivver |

There is a great deal of controversy over Richard Byrd's claim to be the first to fly over the North Pole in 1926 but no matter the ultimate truth, the expedition was financed by Edsel Ford and Byrd named the 1925 Fokker F.VII Trimotor after Ford's daughter Josephine and it is on display at the museum as well.

Although it is not listed as a "highlight" of the gallery, I was impressed by Dayton-Wright Racer, an airplane years ahead of its time when built in 1920. Featuring a clean cantilever wing (no wingstruts) with variable camber and retractable landing gear, it was shipped to France for the 1920 Gordon Bennett Cup air race but a cable failure meant it could not complete the event--the only time it ever participated in an air race!

|

| Note the "RB" logo on the lower cowling. The Dayton-Wright Racer's designers were Howard Rhinehart and Milton Bauman. Pilot visibility was pretty much non-existent. |

Also of particular interest are a pair of rotary wing pioneers. Juan de la Cierva was a Spanish inventor who developed the autogiro, a helicopter forerunner in which the blades are not powered but develop lift with the forward motion of the aircraft, enable very short take-offs and landings but not true vertical ones. A license was to manufacture Cierva autogiros in the United States was obtained in 1928 by Pitcairn Aircraft, a builder of mailplanes, and received considerable publicity as it produced a line of autogiros. In 1931, the Detroit News purchased a PCA-2 for use as a news aircraft and this aircraft is on display in Dearborn.

The next step in rotary-winged flight was the true helicopter and the Henry Ford Museum has a true jewel in that it exhibits the first truly practical helicopter, the 1939 Vought-Sikorsky VS-300A, which first flew on September 14, 1939. It has been in the museum since 1943, except for a return to Sikorsky Aircraft for restoration in 1985.

Now, turning away briefly from transportation machinery, we came across a showcase that featured Henry Ford's violins. This came as a surprise because while I knew that he was keen on old-time dance music and liked fiddles, even learning to play a bit, once he was fabulously wealthy he could indulge his interest more broadly. In addition to building a fancy ballroom, Lovett Hall, for dances, he acquired a number of remarkable violins.

It was clear that these were indeed very fine instruments and looking at the labels I discovered two Stradavari violins from that master's "Golden Age," an Amati and a superb Guarneri del Gesu. Henry Ford would loan them out to anyone who admired them. It is unfortunate that they are now in this showcase unplayed. Even stranger is to think of them being used for country dances and a rousing chorus of "Turkey in the Straw!"

Cremona violins are great (even if not exactly "American Innovation") but if you go to the Henry Ford you should expect a really good collection of automobiles and in this respect there is no disappointment when you enter "Driving America."

|

| 1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout: Henry's Job No. 1 |

|

| 1865 Roper Steam Carriage |

Early on Henry Ford became very interested in racing cars as a way to attract investors. After his first company, the Detroit Automobile Company, failed he set out with associates to build a new car to get attention. In 1901 he raced his "Sweepstakes" car against established manufacturer Alexander Winton at a dirt horse racing track in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, and, to everyone's surprise, won the 10 miles race. He sold the car in 1902 but bought it back in the 1930s, installing a reproduction body. It served its purpose as soon after the race Henry Ford had new backers and a new company, the Henry Ford Company.

|

| 1901 Sweepstakes Racing Car |

|

| 1902 Ford 999 Racing Car

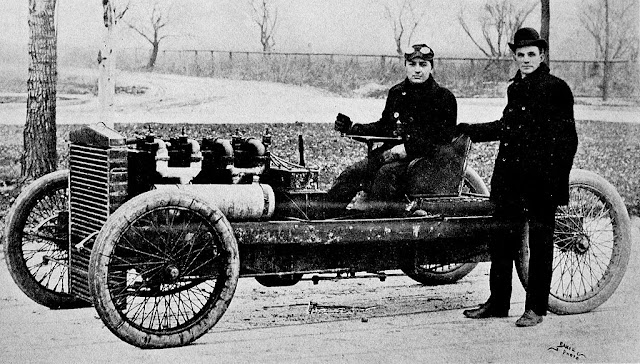

Newly relaunched, Henry Ford continued to disappoint his backers as he worked further on racing cars rather than the practical passenger cars they were hoping he would develop. The result was a pair of racing cars, the famous 999, named after a famous steam locomotive of the day, and a sister car, the Arrow. These were brutally primitive cars,weighing 2370 pounds and having a massive 1156 cubic inch inline four cylinder engine (roughly triple the displacement of the 6.2 litre V-8 in my Corvette), no transmission or suspension, and a single brake acting on the rear axle. Afraid to drive the car (with good reason, I think!), Henry Ford hired the celebrated bicycle racer Barney Oldfield, who bought the car for $800 and raced successfully against the luckless Alexander Winton in the Manufacturers' Cup Race in October 1902. The story goes that Oldfield had only learned to operate the car the morning of the race, never having driven a car before!

Barney Oldfield at the tiller of 999, with Henry Ford, December 1902

In any event, while the car brought fame to Henry Ford, it did nothing for his partners and he was soon out of his second company, which was renamed the Cadillac Automobile Company, but he was allowed to use his name for his next venture, the still-existing Ford Motor Company. Third time lucky!

Henry Ford achieved immortality (and staggering wealth) with his legendary Model T (please see my posting on the Ford Piquette Avenue plant where it was developed) and the museum has an unusual take on this famous car. There is an exploded Model T, showing the simplicity of the design.

Nearby is a really fun exhibit: every day a Model T is assembled by visitors and then disassembled in preparation for the next day! When we visited the car was completed (for something like the 2500th time) but at least I was able to sit in a Model T for the first time.

|

|

| 1913 Scripps-Booth Rocket Cyclecar Prototype, constructed in Detroit |

The early days of the automobile saw a lot of innovation and experimentation. The Henry Ford Museum features some of these developments, including steam and electric cars. The Woods Motor Vehicle Company of Chicago, concerned about the declining sales of its electric vehicles, came up with a hybrid gasoline-electric car in 1916, supposedly to take advantage of the best aspects of each power system, but the company was gone by 1918.

|

| 1916 Woods Dual-Power Hybrid Coupe |

In the early days of motoring, roads in the United States were pretty terrible (if they even existed) so it took brave souls to undertake long-distance adventures. The museum has the second car to cross the United States, a 1903 Packard Model F, which took 61 days to get from San Francisco to New York. It was driven by the Packard plant foreman (accompanied by a journalist), who remarked about the journey: "It was hard, very hard, and I do not care to make the trip again."

|

| 1903 Packard Model F Runabout |

Motor vehicles advanced at a remarkable rate. A very nice display covered the gamut of luxury cars, from an early Rambler limousine to the great cars of the 1930s to the 1956 Continental Mk II.

|

| 1931 Bugatti Type 41 Royale Convertible, one of the six extravagent Royales built |

|

| 1931 Duesenberg Model J Convertible Victoria, body by Rollston |

"Driving America" is divided into different themes, so in addition to early cars, racers, and luxury cars there is a section on design, which includes the Chrysler Airflow, the Tucker 48 and other ground-breaking forms. I am particularly fond of the original Lincoln Continental, conceived by Edsel Ford, and the 1941 example was his personal car, used until his untimely death in 1943.

|

| 1937 Chrysler Airflow Sedan, the final year of production of this short-lived model |

|

| 1948 Tucker Sedan |

|

| Edsel Ford's 1941 Lincoln Continental Convertible |

These are only some of the highlights of "Driving America," and here are some other favourites:

|

| 1906 Thomas Flyer Touring Car, a very high quality vehicle produced by the E.R. Thomas Company of Buffalo, New York, and to become famous in 1908 when one of Thomas' cars won the New York-Paris Race |

|

| 1906 Rapid 12 passenger bus, produced in Pontiac, Michigan. GM bought up stock in the company and by 1912 it formed part of the General Motors Truck Company (now the GMC brand) |

The museum has far, far more to be seen including Early American furniture, the chair Lincoln occupied the night he was shot at Ford's Theater, a massive range of stationary steam engines, including a very early Newcomen Engine, all kinds of farm equipment, and steam trains.

And rounding up this quick overview of our day at the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, what could be better than the wacky Dymaxion House conceived by the inventive Buckminster Fuller?

Developed to address perceived shortcomings in house design, it was meant to be produced in a factory and assembled as a kit on site--on any site. The prototype was manufactured by the Beech Aircraft Corporation, that had experience in aluminum construction and hoped to diversify as the market for light aircraft collapsed in 1948. For various reasons the Dymaxion did not catch on but exhibits many interesting ideas, including prefabricated bathroom modules. It was donated to the Henry Ford Museum in 1990 and after painstaking reconstruction became an exhibit in 2001. You can take a virtual tour of this intriguing house here

.

Our afternoon at the Henry Ford Museum flew by and we did not manage to see everything. I would highly recommend it as one of the more imaginative places to visit!

No comments:

Post a Comment